A/B roll editing is a fundamental approach to preparing original film elements for printing. Although most commonly associated with 16mm film, A/B roll editing has been used in other gauges, and became common eventually in 35mm commercial production as a higher quality alternative to producing effects such as fades or dissolves (versus the previous typical practice of creating these kinds of effects in a separate duping stage, which added two generations of quality loss to the footage needing the effect).

Although I may eventually have more information here regarding actual A/B editing process and techniques, I feel like that info is pretty easily findable in a lot of places (I’d recommend Lenny Lipton’s book Independent Filmmaking, for this and many other pieces of invaluable information). Instead, I’ve been curious to try to chart the historical development and use of A/B roll editing. Where did it originate? Is it known who first came up with it as an approach? Presumably, it would only have been adopted a bit more widely once commercial labs identified it as a process worth offering, so does that mean that initially it was a limited, boutique practice only used in-house by one or more production companies…?

This last question may be answerable, sort of. I’m still digging into old magazines for more information, but there is some evidence that a partial origination of A/B roll editing may be with The Calvin Company, a production company specializing in educational/industrial films based in Kansas City, MO. Calvin was founded in 1931, and were one of the major producers of educational and industrial films for a few decades, as well as an important influence on the use and professionalization of 16mm as a viable and high quality format for production and dissemination. Through their commitments to 16mm based on its economy and versatility, the company innovated a number of techniques that became standardized in 16mm production. It seems fairly likely that A/B roll editing – or at least a variation of it – was one of those techniques.

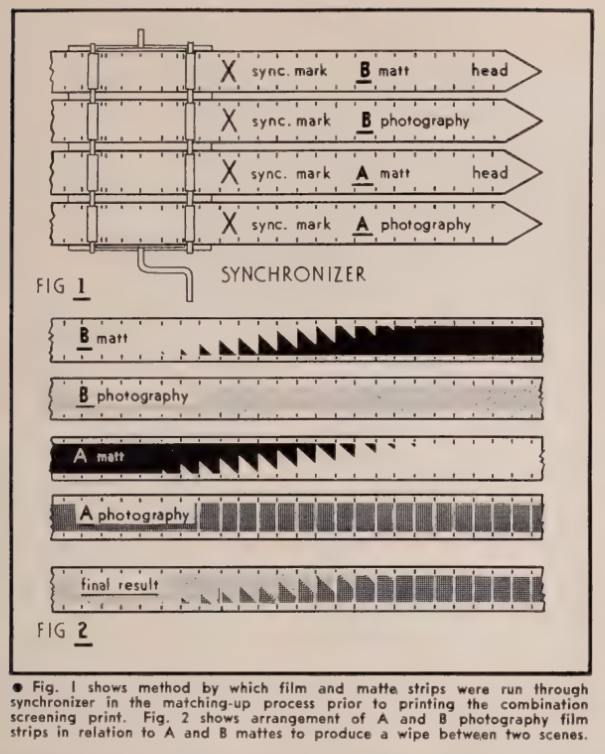

Larry Sherwood (Director of Productions at Calvin) presented a talk at the Fall 1942 SMPE meeting in New York, entitled, “Editing and Photographic Embellishments as Applied to 16-mm Industrial and Educational Motion Pictures”. This talk was later published as an illustrated article in the December 1943 issue of SMPE’s Journal. Among other innovations and approaches described in the article, Sherwood explains Calvin’s method for using A/B roll picture rolls in combination with A/B “mat” (i.e. matte/masking) rolls to create wipes and other effects without needing to make an optical dupe. The A photography roll was printed in bi-pack with the A “mat” roll onto the raw stock. When no matte effect is needed, the “mat” roll is clear leader, allowing light to pass through to only reproduce the A photographic roll onto the raw stock. When, for example, an A->B wipe is needed, the A “mat” roll would contain a high contrast animated matte effect, whereas the B “mat” roll would contain a negative version of that same matte effect. By printing the A photography+mat rolls in bi-pack, then winding the raw stock back and printing the B photography+mat rolls in bi-pack, the resulting film would achieve a composited matte effect.

From Sherwood’s article:

“It is somewhat difficult to explain the method of procedure, yet in reality it is extremely simple. The original photography will be edited into two strips of film, which for convenience we will call A and B. The mats will also be edited into two strips of film, coinciding with the A and B photography. …

“To the leader of mat A is spliced a strip of transparent film, which in the printing process will allow the light to pass through this mat and print the scene on photography A on the raw stock. On photography B there is spliced the normal leader film, which in the case of exposed film is yellow in color [MT note: he means lightstruck leader]. On mat B there is spliced a strip of black film. This black film is produced merely by running the exposed film through normal processing [MT note: black leader]. The result is that the yellow leader on photography B will be blacked out. …

“There is an overlap of 2ft in photography A and B. Now, to insert a mat: these mats can be made up in any form the imagination can develop – lap dissolves, straight vertical wipes, horizontal wipes, circle wipes, etc. For clarity, let us assume that a straight left to right vertical wipe, or effect, is wanted between the first and second scenes. This straight wipe consists of two pieces of film, one negative and the other positive. These mats are matched so that wherein A has a clear portion of film, B will have a black portion [MT note: i.e. these are hi-con animated matte effects comprising a positive and negative version, respectively]. …

“In the printing process, photography A and mat A are run synchronously and the light of the printer is allowed to pass through mat A and through photography A, exposing the picture on the raw stock. In other words, wherever mat A is clear and there is a picture on photography A, that picture will be transferred to the raw stock. …”

I’m pre-empting the rest of the text and inserting myself here, because this is such a new concept/process being described, and it’s not being done in the most clear or eloquent way, both because the writing is a bit cumbersome and overdone, and it’s also speaking to a 1943-era technical audience with different knowledge bases and reference points than we have now, with our retrospective knowledge. (No offense meant to Mr. Sherwood!) But essentially what Sherwood is describing is what we might now think of as a bi-pack printing process, where the A-roll has a corresponding a bi-pack matte roll that will occasionally introduce animated wipe effects made on hi-con film, for which there’s a corresponding reverse polarity copy in the B-roll matte. It’s really the same concept as making a wipe on an optical printer, but the bi-pack and A/B approach enable it to be done without extra steps/generations in printing.

The article’s discussion of A/B editing tends to focus specifically on wipes, but the mention of “lap dissolves” is important here, because the A/B overlap described enables a shot on the A-roll to be dissolved with a shot on the B-roll. However, it’s not clear how they precisely accomplished this. For example, would it have been done with a light/fader/voltage adjustment to bring the lamp down or close an iris to diminish exposure for the fade out? Or was another kind of matte used that had a gradated exposure ramp from clear to black, and vice versa? Calvin had its own lab and printed their own films, so it’s possible or even likely they had customized equipment to achieve their various technical needs.

A few years later, the September 1947 issue of Home Movies contains an article by amateur filmmaker Victor Duncan called, “Transitions by Mattes and Printing”. In discussion the production of his film, Duncan makes a short reference to A/B printing, and specifically calls it “A & B roll printing”, also attributing his knowledge of the technique to the Larry Sherwood SMPE Journal article (and in fact, this is how I found the Sherwood article myself). Additionally, the fact that Duncan refers to A & B roll editing as how “most professional productions are completed” is suggestive that by 1947, the practice was more widely known and employed:

“From the beginning, I had planned to introduce effects into the picture by means of printing with travelling mattes. The purpose of matte printing was not necessary; in fact, it was more expensive. But I wanted to edit the picture into A & B rolls for experience. Most professional productions are completed in such a manner, and I wanted to see if I couldn’t make a picture the same way. Some day I may need to know how to do it. The mattes were photographed on a homemade title board with squares of black-and-white cardboard. The process of editing film for A & B roll printing is described by Larry Sherwood in the ‘Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers,’ December, 1943. My first knowledge of editing for effects was the information I obtained from Sherwood’s article, and my equipment is far from professional. A friend made my synchronizer from projector sprockets.

“By the time all my footage had been returned from the processing laboratory, I was discharged from the service. Therefore, I edited the picture at home in Dallas, and the Calvin Company in Kansas City printed the picture from my mattes.”

I’ve cited this article because it shows that, by 1947, the A/B method was known to some amateur filmmakers, but perhaps not used much by them. The fact that Duncan had his film printed at Calvin suggests that A/B printing (or at least A/B printing with A/B matte rolls) may have still been a specialty process that only Calvin and perhaps a few other labs would have accommodated. Additionally, the model for Duncan’s method seems still to be the Calvin approach which incorporates this matte-roll aspect, rather than just photographic rolls alone. The curious thing about this Calvin approach to A/B editing is the dependence on matte rolls. Essentially this would eventually be dispensed with and wipes or other optical effects would be relegated primarily to optical printers, which became more accessible to independent and experimental filmmakers via optical houses or even artists doing their own opticals if they had access to a printer. A/B editing eventually became primarily used for invisible splicing, fades, dissolves, and superimpositions.

From my own first hand archival experience, the earliest two films I can think of that employed A/B editing without additional matte rolls are Flora Mock’s Waiting (1952) and Stan Brakhage’s The Way to Shadow Garden (1954). I’ve also inspected the Kodachrome 16mm original A/B rolls for the 1946 independent feature film The People’s Choice, which is definitely the earliest film by far I’ve encountered first hand that was cut as A/B rolls.

This page will likely be added to and re-organized as I come across additional information on A/B editing, but at least for now, I wanted to include these early references as a starting point.